Most film historians say that “film noir” is a cinematic movement that began in 1940 with Boris Ingster’s little-seen film “Stranger on the Third Floor” (staring Peter Lorre) and ended in 1958 with Orson Welles’s “Touch of Evil.” The roughly 300 films released during this period that make up the genre share a sensibility of narrative, political, stylistic, thematic, and visual elements. French film theorists originally coined the term in 1946 to describe a group of films that included “The Maltese Falcon” (1941), “Double Indemnity” (1944), and “Laura” (1944). Though an American phenomenon, many of Noir’s filmmakers hailed from throughout Eastern and Western Europe – many on the run from fascism. Little did they know that right-wing extremism would follow them across the ocean to America’s social and political stage.

Most film historians say that “film noir” is a cinematic movement that began in 1940 with Boris Ingster’s little-seen film “Stranger on the Third Floor” (staring Peter Lorre) and ended in 1958 with Orson Welles’s “Touch of Evil.” The roughly 300 films released during this period that make up the genre share a sensibility of narrative, political, stylistic, thematic, and visual elements. French film theorists originally coined the term in 1946 to describe a group of films that included “The Maltese Falcon” (1941), “Double Indemnity” (1944), and “Laura” (1944). Though an American phenomenon, many of Noir’s filmmakers hailed from throughout Eastern and Western Europe – many on the run from fascism. Little did they know that right-wing extremism would follow them across the ocean to America’s social and political stage.

A moody cynicism about the scales of justice and America’s flawed postwar capitalist system are running themes. These reflect an America recovering from the Great Depression, only to emerge in World War II, which gave way to the Cold War. The archetypical American Dream of the ‘50s is not part of the Noir equation. Noir’s alienated characters are naturally distrustful, seen-it-all, people out to salvage what they can from a ruthless society. They fight dirty. They’re survivors — but they jealously guard their individuality. Death is always just around the corner for characters ready to go out with their sex drive, dignity, intellect, wit, and stylish charm intact. Guns, cigarettes, booze, and sleazy hotel rooms — many of the scripts were adapted from pulp fiction magazines — come with the territory.

As its name implies, the visual aspects of film noir emphasize the high contrast between the black and white extremes of the film stock used predominantly during the period. German Expressionist cinema (reference “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” – 1923) was influential on cinematographers attempting to capture a dislocated sense of social isolation that defined characters whose motivations are often centered around their need to escape.

Significant too is the “pulp” literary tradition, which gave noir its grittiness with an underworld environment in a country whose repressive influences are always lurking in the shadows. Such shadows allowed noir filmmakers to play with a built-in image system of white light penetrating into claustrophobic interior and exterior spaces. Writers such as Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Kames M. Cain, and Cornell Woolrich provided a “hard-boiled” template for plot and dialogue that Noir filmmakers mined for every bit of narrative gold they could.

The advent of the Kodak Eastman Color process in 1952 contributed to the ultimate demise of film noir, though not all Classic Film Noirs were filmed in black and white. Kodak provided a quicker and more economic alternative to the Technicolor system that had been used as far back to the 1920s for such high-budget films such as “The Wizard of Oz” and “Gone With the Wind” (1939).

Politically, the demise of Film Noir can be traced back to Senator Joseph McCarthy’s House on Un-American Activities Committee, whose witch-trials resulted in the blacklisting many of the screenwriters, actors, and directors responsible for keeping Film Noir going. Noir filmmakers such as Edward Dmytryk (“Crossfire” – 1947) and John Berry (“He Ran All the Way” 1951) were exiled from making films in America along with other members of the “Hollywood Ten,” whose creative potentials were cut short by the same repressive cultural and economic system they had so fiercely commented on. (Introduction written by Cole Smithey)

After the jump, is our final list covering the Top Ten Films Noir.

Ranked List, Part 5

- The Big Heat (1953, Fritz Lang)

Film noir has rarely been darker than The Big Heat. Fritz Lang’s gripping 1953 masterpiece is a film in which actions have dire consequences, and the director doesn’t shy away from the shattering effects of violence. Glenn Ford is Bannion, a good cop in a dirty town, whose obsessive pursuit of justice and overwhelming desire for revenge impacts upon everyone who comes into contact with him. A car bomb meant for Bannion instead kills his wife and daughter; a murder victim’s widow winds up dead; and—in the film’s most infamous moment—a brutal gangster uses a hot pot of coffee to punish his moll. The victim in this shocking scene is played by Gloria Grahame, who is introduced as a narcissistic character prone to admiring her own beauty in mirrors, which makes it cruelly inevitable that Lee Marvin’s Vince Stone should attack that very quality so savagely. Even those who survive the violence that cascades through this film walk away from it bearing deep scars that can’t be hidden in the shadows that Lang and the great cinematographer Charles Lang (no relation) manipulate so potently. The Big Heat has a relentless sense of forward momentum, which reflects the single-minded obsessiveness of Bannion’s mission, but even as we might will this protagonist to bring the criminals to justice, Lang makes it clear that there will be no sense of catharsis in his ultimate victory. The damage has been done. (Philip Concannon)

- The Night of the Hunter (1955, Charles Laughton)

Noir, Southern gothic, horror, coming-of-age, and expressionism combine in Charles Laughton’s unclassifiable 1955 masterpiece. In Depression-era West Virginia, Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum), a preacher of no specific Christian denomination and serial killer of no more specific a prey, takes a chance that his death-sentenced cellmate hid a large loot with his young children, and sets upon marrying their now-widowed mother. What begins as a familial thriller gradually morphs into something stranger, more haunting, filled with impossible questions and uneasy answers.

Mitchum’s command of the picture is so total that much of it is as much a reflection of his character’s twisted psyche as Laughton’s vision, as though each so thoroughly invested in it that all three became inextricably linked. Yet, Powell is not the main character of the film; the children are. Billy Chapin (as John, the older son) and Sally Jane Bruce (as Pearl, his younger sister) barely acted after this picture, and while neither give revelatory performances, his inherent honesty and her otherworldliness are beautiful extensions of the film’s deeper tension between an honest, humble living and more theatrical corruption. John is old enough to have foundational loyalties, but Pearl’s are still very much being formed. Their journey downriver, as transportive and purely cinematic as Kubrick’s “Beyond the Infinite” sequence from 2001, binds them permanently to one another, tied by their shared trauma, yes, but more powerfully by their dedication. Most of the adults come to disappoint them, but children can survive anything. Of all the questions the film piles on—logical, moral, psychological—Lillian Gish’s assurance that “children are man at his strongest” is by far the most overtly-stated answer, and the only one that truly matters. All else is understood intuitively, or left nagging in the night. (Scott Nye)

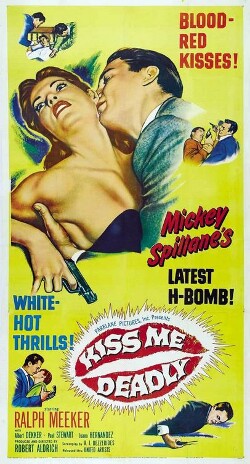

- Kiss Me Deadly (1955, Robert Aldrich)

One of the definitive film noir pictures, Robert Aldrich’s masterpiece blends Cold War paranoia with a percussive and brazen lead performance from Ralph Meeker. As bleak as the genre comes, the film is gorgeously shot from the underrated Aldrich, who allows the lead performance from a searing Meeker, taking on the legendary role of Mike Hammer, to truly take over a film that is as timeless today as it is a time capsule of ‘50s American paranoia. Written by black-listed screenwriter A. I. Bezzerides, the film is of its time, but the greatness surrounding this picture is its ability to stand the test of time. From the performances (including turns from the likes of Maxine Cooper and Cloris Leachman) to the photography from Ernest Laszlo, the film plays just as daring and, truly, dangerous as it did when it first hit theaters. Feeling like a breath of fresh air to this very day, the film plays like a punch to the gut. However, no matter how bleak this picture gets, it remains one of the greatest examples of just how potent a genre film noir was, and how, at its best, it plays on the purest of emotional states. Even if there are inexplicable, seemingly otherworldly elements and some dangerous dames, this is as close to a mirror being thrust in front of ‘50s America as film noir ever produced. Kiss Me Deadly is simply one of the greatest pictures of the genre ever committed to celluloid. (Joshua Brunsting)

- The Big Sleep (1946, Howard Hawks)

As one of the shining jewels of the noir genre, The Big Sleep epitomizes the notion of style becoming substance. The plot is so convoluted that director Howard Hawks and star Humphrey Bogart supposedly called author Raymond Chandler in a drunken stupor one night to ask about a specific story point. Chandler couldn’t tell them. Whodunit doesn’t matter so much in The Big Sleep as how they dun it, as well as the cool, collected private eye who slowly works his way to the heart of it all. It doesn’t hurt that the private eye in question is Philip Marlowe—the epitome of the type—or that he’s played by Bogart in the role he was born for. He strides through the morass of a case with a quip always at the ready, backed up by a swift right whenever anyone feels like talking back. His path leads through the seamy street of a thoroughly corrupt Los Angeles, rife with hidden agendas, shattered dreams, and human wolves eager to gobble up the unwary. Against that, Marlowe’s battered-but-unbroken ethics serve as his sword and shield, keeping him on course even when the city’s assembled temptations rise up to crush him.

To paraphrase the late Roger Ebert, The Big Sleep celebrates the process of Marlowe’s investigation instead of the results, which is as apt a way to describe noir as anything. We relish the steps along the way, the clever games Marlowe plays with his quarry, and the implied sex and violence that were positively shocking at the time. The answers, it tells us, matter much less than the manner in which we ask the questions, and in the world of noir, no answer can provide peace anyway. The Big Sleep understands this as few other films ever have, and in so doing, elevated itself to the ranks of the genre’s elites. (Rob Vaux)

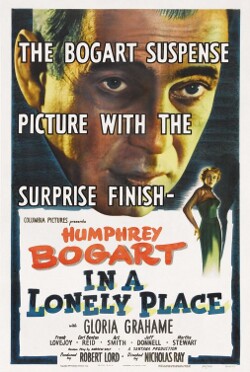

- In a Lonely Place (1950, Nicholas Ray)

In the opening scenes of In a Lonely Place, an inebriated Dixon Steele (Humphrey Bogart) muses to a waiter, “There’s no sacrifice too great for a chance at immortality.” This line tends to get a laugh with audiences, but it cuts straight to the core of Nicholas Ray’s existentially-tinged, morally fraught masterpiece, even as the ensuing series of unfortunate events devastatingly proves otherwise. A has-been screenwriter with a chance to make it to the big leagues once again, Steele gets caught up as a murder suspect when a woman is found dead but an hour after leaving his apartment; whether or not he is guilty of the crime is ultimately beside the point as unlucky circumstances and his own stubbornness stack the odds against him. The rage of the troubled artist brims over terrifyingly in Bogey’s haunting (and haunted) performance, perhaps the most overlooked of his career, and Ray’s film encapsulates the heartbreak of a genre in which good intentions amount to little in the face of a cruel world. A cigarette, a ring, a phone call; sometimes, it’s the simplest things that can make the difference between happiness and despair, but one senses that Steele was doomed long ago, whatever his present choices. Some have criticized the film for supposedly pulling its punched in its final moments, but it seems much more devastating to have to go on filled with regret with what could have been: innocent, but jailed forever in one’s own torment. In other words, alive, but essentially dead inside. (Rob Humanick)

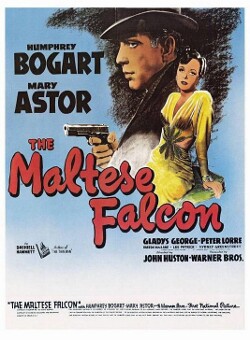

- The Maltese Falcon (1941, John Huston)

A knockout dame walks into Sam Spade’s office with what should be a simple job, but soon stiffs start turning up, along with an exotic cast of characters all searching for the fabulous Maltese Falcon. Often considered the first film noir, Falcon sets the formula future movies will follow, from the shadowy cinematography to the crisp patter, double-crosses and convoluted plotlines. The Maltese Falcon mainly impresses thanks to its one-in-a-million cast of rogues. Humphrey Bogart’s hard-drinking, quick-thinking Spade must play each of the villains—neophyte tough guy Wilmer (Elisha Cook, Jr.), dainty Joel Cairo (Peter Lorre), lovely and duplicitous Brigid (Mary Astor), and imposing Gutman (a debuting Sidney Greenstreet)—off against the others. Tiny physical details bring each of the characters to life: the way Cairo caresses his phallic cane, the way Spade looks down and is amused to find his hand trembling after he’s risked his life in a gambit to intimidate Gutman. Spade eschews guns—and the law, and emotional intimacy—relying solely on his own wits to survive. The detective stands down the decadent European fortune-hunters, foreign interlopers on the streets of his Chicago, with homegrown American ingenuity, but he himself has a core of corruption. He’s sadistic (“When you’re slapped, you’ll take it and like it!”), an adulterer, and a very bad friend to his partner Archer; he has a code of honor, but he enacts it joylessly. He’s an antihero with enough charm to sneak his bad behavior past the Production Code. With its heartless, bitter conclusion, this isn’t hopeful, rally-the-troops, sacrifice-for-the-greater-good propaganda like Bogart’s subsequent patriotic turn in Casablanca. The Maltese Falcon is presciently cynical—the kind of film that seems like it would have been made after the atom bomb dropped. (Gregory J. Smalley)

- Out of the Past (1947, Jacques Tourneur)

“Don’t you believe me?” “Baby, I don’t care.” Robert Mitchum’s iconic combination of weariness and unflappable resolve produce perhaps his finest vintage performance in Out of the Past, a fleet and nasty noir that prompted James Agee to observe of the star’s tete-a-tetes with women, “When he slopes into clinches you expect him to snore in their faces.” As a onetime private eye running a rural gas station under an alias when the shabby characters who laid him low pull him back into a sinkhole of violence, Mitchum almost never breaks a sweat, whether revealing his sordid history to his small-town sweetheart in flashback or coolly negotiating with a menacing client, a wealthy, crisply witty hood (Kirk Douglas with few of his usual hyperventilating mannerisms). A prototype among postwar tough guys, Mitchum’s Jeff Markham is a survivor boiled down to the essentials, telling the cunning femme fatale played by Jane Greer that “if I have to (die) I’m gonna die last.”

Adapted by Daniel Mainwaring from his novel Build My Gallows High, and helmed by Jacques Tourneur after his string of evocative low-budget “horror noirs” like Cat People, Out of the Past adds up to more than baroque angles and chiaroscuro lighting, though there’s a shadowy indoor fistfight that’s interrupted by a game-changing blast from Greer’s pistol. As Mitchum parries the malevolent moves of man-trap Greer and smug thug Douglas, aided by a deaf-mute teen and a San Francisco cabbie, his resourcefulness only delays the self-realization that he sealed his fate one seductive night in Acapulco. Unable to hide from it in the sunny ravines of the Sierra Nevada or escape it in a mayhem-riddled odyssey through the underworld, he knows no way to win, just “to lose more slowly.”(Bill Weber)

- The Third Man (1949, Carol Reed)

The Third Man is nne of the best film noirs for its realism, humor, and story, but also for its skewed approach. Holly Martins, a writer of cheap fiction, seems to know that he is in a film noir and acts like a heroic PI despite having absolutely no idea what is going on (at one point he hilariously mistakes his chauffeur for a kidnapper). He is the ultimate amateur detective, hopelessly naïve and gamely, often drunkenly, wandering through the story while other peoples’ lives are ruined. A subplot involving Alida Valli is the film’s real heart; the men run around with guns in sewers while Valli’s life is ruined by heartbreak and the all-too-real threat of deportation. One great scene sums this up beautifully: Martins blithely antagonizing the police while Valli desperately tries to shut him up, knowing that the consequences can be so much worse for her than for him.

Another oddity is the film’s interest in post-war Vienna, barely functioning under widespread crime and four different police forces that can barely communicate. The ruins of Vienna are evocatively presented, giving the constant impression that there is a lot going on just beyond the parameters of the story, one which plays out so casually that the big twists and turns seem almost irrelevant. Reed increases the confusion with tilted frames, cock-eyed perspectives and by coupling the images with Anton Karas’ brilliant zither score, which will stay in your head for days. All of this is great, but little compared to the appearance of Orson Welles in what is surely one of the best character introductions in film history. Not to mention one of the best monologues, improvised by Welles, and one of the best final shots, powerfully expressive of heartbreak, longing and the end of a romance. (Matthew McKernan)

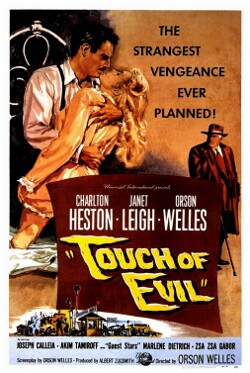

- Touch of Evil (1958, Orson Welles)

After a ten year exile from directing in Hollywood, Orson Welles found himself once again in the position to make a studio picture out of a pulp thriller. He made the project his own, a baroque murder mystery in the border town netherworld straddling the boundary between Mexico and the good old U.S. of A. turned into a mad, gloriously sleazy and grandiosely bravura Hollywood crime opera, a study in corruption and racism. Charlton Heston is a stiff, straight-arrow Mexican government agent whose planned honeymoon with his American bride Susie (Janet Leigh) is derailed by a sensationalistic murder and a blustery American police detective (Welles) with a doughy face and an ill manner.

Welles turns studio sets and locations shot in Venice, CA, into a dark, seedy labyrinth with stunning camerawork work (including his legendary opening take) and the most startlingly modernist cutting to grace a studio film, and turns his cherubic face into the bloated bulldog mask of bullying Hank Quinlan, perhaps his most grotesque figure in a career of power mad manipulators. A dynamic and unconventional mix of rock and roll and Latin sounds scored by the then unknown Henry Mancini adds to the nervous energy. The film was taken from Welles in the editing room and released in a compromised version, and then decades later reconstructed into “ideal form.” Welles supervised none of these versions, yet his vision cuts through them all: Touch of Evil a sleazy, grimy, jittery, and ultimately dazzling work of cinematic magic and the final masterpiece of the classic noir era. (Sean Axmaker)

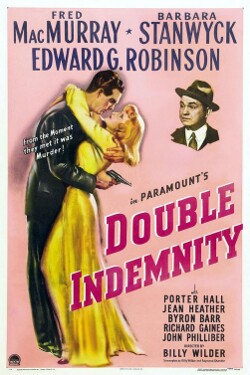

- Double Indemnity (1944, Billy Wilder)

Before she ran The Big Valley and before he had My Three Sons, Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray generated enough sexual electricity to light up Los Angeles as the accomplices in crime of Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity. There’s not a noir that crackles with better or more sexually charged dialogue than this one. The two circle each other like a predator and its prey. In one respect, MacMurray’s Walter Neff is no match for the ruthless determination of Stanwyck’s Phyllis Dietrichson. With severe blonde bangs framing a luscious face, Phyllis approaches Neff like an expert fisherman eying an attractive catch; her shiny anklet is the initial bait that lures Neff in. Then he falls hook, line and sinker, unable to wriggle free no matter how hard he struggles. But he doesn’t struggle too hard. For all his talk of trying to do the right thing, he can’t deny his attraction to Phyllis and all her rottenness. He knows Phyllis promises nothing but danger but he goes along anyway, turning his back on a career built on integrity and responsibility. Noir presents its dark world as a seductive alternative to the American mainstream and its dull status quo. But Phyllis, in all her careful calculations, doesn’t count on one thing – a reluctant and fatal mutual attraction. Wilder defined the noir world as one of harsh shadows and light, moral ambiguity, and a palpable sexual tension. It’s a world we simply can’t resist. Double Indemnity needs to be one of the film noirs that gets put in a time capsule to let future generations know exactly what the best of the genre was. (Beth Accomando)