Most film historians say that “film noir” is a cinematic movement that began in 1940 with Boris Ingster’s little-seen film “Stranger on the Third Floor” (staring Peter Lorre) and ended in 1958 with Orson Welles’s “Touch of Evil.” The roughly 300 films released during this period that make up the genre share a sensibility of narrative, political, stylistic, thematic, and visual elements. French film theorists originally coined the term in 1946 to describe a group of films that included “The Maltese Falcon” (1941), “Double Indemnity” (1944), and “Laura” (1944). Though an American phenomenon, many of Noir’s filmmakers hailed from throughout Eastern and Western Europe – many on the run from fascism. Little did they know that right-wing extremism would follow them across the ocean to America’s social and political stage.

Most film historians say that “film noir” is a cinematic movement that began in 1940 with Boris Ingster’s little-seen film “Stranger on the Third Floor” (staring Peter Lorre) and ended in 1958 with Orson Welles’s “Touch of Evil.” The roughly 300 films released during this period that make up the genre share a sensibility of narrative, political, stylistic, thematic, and visual elements. French film theorists originally coined the term in 1946 to describe a group of films that included “The Maltese Falcon” (1941), “Double Indemnity” (1944), and “Laura” (1944). Though an American phenomenon, many of Noir’s filmmakers hailed from throughout Eastern and Western Europe – many on the run from fascism. Little did they know that right-wing extremism would follow them across the ocean to America’s social and political stage.

A moody cynicism about the scales of justice and America’s flawed postwar capitalist system are running themes. These reflect an America recovering from the Great Depression, only to emerge in World War II, which gave way to the Cold War. The archetypical American Dream of the ‘50s is not part of the Noir equation. Noir’s alienated characters are naturally distrustful, seen-it-all, people out to salvage what they can from a ruthless society. They fight dirty. They’re survivors — but they jealously guard their individuality. Death is always just around the corner for characters ready to go out with their sex drive, dignity, intellect, wit, and stylish charm intact. Guns, cigarettes, booze, and sleazy hotel rooms — many of the scripts were adapted from pulp fiction magazines — come with the territory.

As its name implies, the visual aspects of film noir emphasize the high contrast between the black and white extremes of the film stock used predominantly during the period. German Expressionist cinema (reference “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” – 1923) was influential on cinematographers attempting to capture a dislocated sense of social isolation that defined characters whose motivations are often centered around their need to escape.

Significant too is the “pulp” literary tradition, which gave noir its grittiness with an underworld environment in a country whose repressive influences are always lurking in the shadows. Such shadows allowed noir filmmakers to play with a built-in image system of white light penetrating into claustrophobic interior and exterior spaces. Writers such as Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Kames M. Cain, and Cornell Woolrich provided a “hard-boiled” template for plot and dialogue that Noir filmmakers mined for every bit of narrative gold they could.

The advent of the Kodak Eastman Color process in 1952 contributed to the ultimate demise of film noir, though not all Classic Film Noirs were filmed in black and white. Kodak provided a quicker and more economic alternative to the Technicolor system that had been used as far back to the 1920s for such high-budget films such as “The Wizard of Oz” and “Gone With the Wind” (1939).

Politically, the demise of Film Noir can be traced back to Senator Joseph McCarthy’s House on Un-American Activities Committee, whose witch-trials resulted in the blacklisting many of the screenwriters, actors, and directors responsible for keeping Film Noir going. Noir filmmakers such as Edward Dmytryk (“Crossfire” – 1947) and John Berry (“He Ran All the Way” 1951) were exiled from making films in America along with other members of the “Hollywood Ten,” whose creative potentials were cut short by the same repressive cultural and economic system they had so fiercely commented on. (Introduction written by Cole Smithey)

After the jump, is the fourth part of our list, ranks 11 to 20. Tomorrow, we’ll present our Top Ten Films Noir.

Ranked List, Part 4

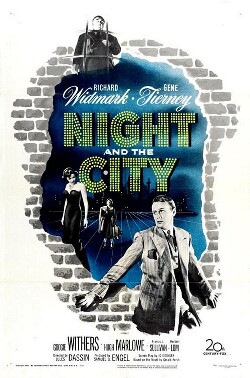

- Night and the City (1950, Jules Dassin)

Redemption is a thematic keynote in much of film noir, and few examples are as unexpected, and therefore as powerful, as the one provided by the climax of Jules Dassin’s archetypally titled classic. Like The Third Man, Night and the City sees an American fumbling through post-war Europe. As Harry Fabian, the manic-yet-precise Richard Widmark is Harry Lime with all of the schemes and none of the grandeur—or luck. As he orchestrates a big-time wrestling promotion scheme, he plays everyone, none more so than girlfriend Gene Tierney. Like the audience, she sticks with him despite her misgivings. Evocatively using London locations so that they both document the specifically real and represent a kind of universal urban underbelly, Dassin makes a convincing poetic argument: the city as that place where dreams can come true if you just angle them the right way, but also a rat’s maze of shadow and threat when they don’t. It’s the same city, after all; only one’s vantage point, or perhaps soul, has changed. (Peter Gutiérrez)

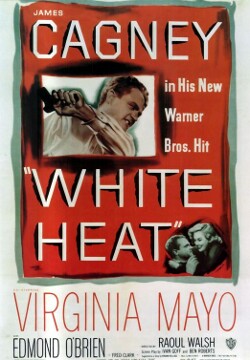

- White Heat (1949, Raoul Walsh)

James Cagney’s final, euphoric cry at the climax of White Heat—“Made it, Ma! Top of the world!”—is so transcendent a moment in cinema that no amount of postmodern references or clip-show rotations can diminish its power. As purely exciting a crime film as has even been produced, Raoul Walsh’s 1949 classic tells the intertwining stories of career criminal Arthur “Cody” Jarrett (James Cagney, in what is arguably his greatest performance) and undercover cop Hank Fallon (Edmond O’Brien), ratcheting up the tension with almost cruel precision until the film’s literally explosive finale. Cagney’s primal, unhinged performance more than sells the insanity of a man for whom murder could be a mere afterthought; it practically leaps off the screen. His character was based in part on the New York murderer Frank Crowley, but White Heat eschews real-life storytelling, instead occupying the stuff of pure Hollywood legend. (Rob Humanick)

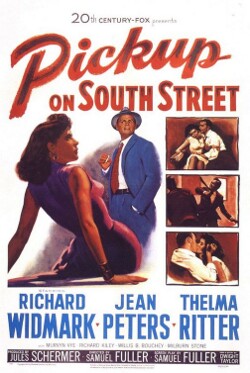

- Pickup on South Street (1953, Samuel Fuller)

Pick-up on South Street is more than a crime drama: it is a window into the era of the red scare and the paranoia that forced ordinary people to do things against their better nature. Richard Widmark stars in a remarkable performance as Skip McCoy, a small-time pickpocket who picks a lady’s purse on a subway one morning. Among his pilfered goods, he later finds a secret microfilm that the woman was to pass on to a Communist contact. As she tries to get the film back, she unwisely falls in love with McCoy as an agent closes in, putting both their lives in danger. Fuller was a master of tough, mean thrillers and here he was at the top of his form, creating a world of fear and panic, murder and commie paranoia. This is more than a thriller; it’s a time-capsule. (Jerry Goran)

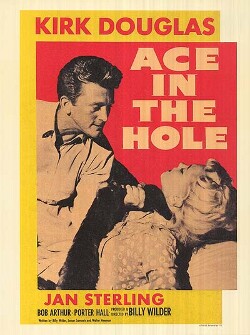

- Ace in the Hole (1951, Billy Wilder)

After a string of successes, Billy Wilder defied Hollywood expectations with a scathing indictment of the American media that still stings today. Wilder based his story on a 1925 media circus. The nation followed the trials of spelunker Floyd Collins, trapped in a vast cave in Kentucky. Collins died, but unorthodox reporter William Burke Miller won the Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the story. In Ace in the Hole washed-up newspaper man Charles Tatum (played ferociously by Kurt Douglas) has been reduced to working for a small paper in Albuquerque. He chomps at the bit for a return to his bygone glory days. Then he stumbles upon the plight of Leo Minosa (Richard Benedict), an unlucky soul who has gotten himself stuck at the bottom of an ancient Indian burial cave. Dollar signs float in front of Tatum’s eyes as he quietly manipulates the story to boost his flagging career.

Originally released as The Big Carnival Wilder’s film-noir vision flaunted cinema conventions with American cinema’s ultimate anti-hero. Douglas delivers desperation and a cynical rejection of humanity that is repulsive as it is mesmerizing. Although not a traditional noir, Ace in the Hole stakes its claim in the genre by building a gathering storm of crass opportunism via a capitalist wormhole whose gray shades of corruption paint nearly every composition. The noir shadows here come from the claustrophobic interiors of Leo’s cramped mountain coffin. Meanwhile, the world outside celebrates his plight, forgetting that a human life hangs in the balance. As thousands gather, the cold insensitive masses belie their commercially charged sense of community. (Cole Smithey)

- The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946, Tay Garnett)

Sex, money, violence and murder take center stage in this deliciously cynical tale about a married femme fatale and the flirtatious drifter who falls under her spell when he stops at the diner owned by the siren’s much older husband. Lana Turner and John Garfield exchange smoldering looks and suggestive double entendres as their characters sink deeper and deeper into the mire of betrayal and retribution. Turner never looked lovelier or more seductive, especially in a sexy shot that slowly pans from her toes to her white-turbaned head. Garfield, who fits his brash role perfectly here, delivers a riveting performance. With its intriguing light-and-shadows cinematography and deft direction by Tay Garnett—from a suspenseful screenplay by Harry Ruskin and Niven Busch—this 1946 movie version of the racy bestselling novel by James M. Cain is film noir at its best. (Betty Jo Tucker)

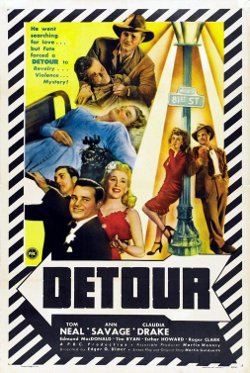

- Detour (1945, Edgar G. Ulmer)

Part of the basic purpose of film noir was to be cheap and raw, but even the most barbarically impoverished production looks lavish next to this Poverty Row masterpiece, a film that frequently appears to have been made for whatever change the assistant director had in his pockets that afternoon, and benefits immeasurably from the totally undiluted realism that results. Following Tom Neal as one of the sorriest dupes who ever got suckered in by a woman (Ann Savage’s deliciously toxic Vera, one of the most fatale of all the genre’s femmes), trapped in a spiral of ever-worsening crimes, it’s one of the most thoroughly fatalistic movies ever put to celluloid, banishing even the fantasy that it’s possible to get through life cleanly. Its intense DIY nihilism is so focused and burning that it proves both simultaneously transcendent and punishing. (Tim Bayton)

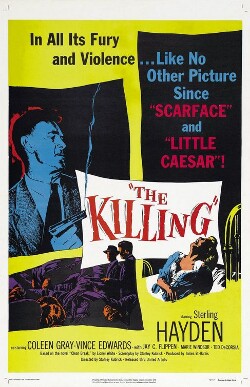

- The Killing (1956, Stanley Kubrick)

Stanley Kubrick made a great film in almost every genre, and noir was no exception. His 1955 film The Killing is at heart a familiar tale of a carefully conceived heist going disastrously off the rails, but it’s elevated into something special by the director’s chronological shuffling and peerless control of mood. Sterling Hayden is Johnny Clay, the man who thinks he has it all figured out, while Coleen Gray is superb as the femme fatale who’s got “a great big dollar sign there where most women have a heart.” When the cracks start to appear in the plot and these relationships, the tension rises inexorably until the unforgettable finale, in which Johnny can only watch in horror as his best-laid plans are blown to the wind. (Philip Concannon)

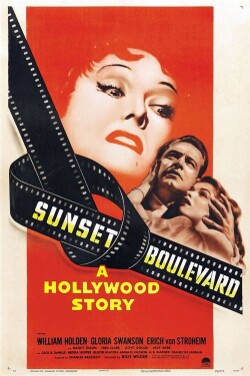

- Sunset Blvd. (1950, Billy Wilder)

The two most instantly recognizable lines of dialogue in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard—“I’m ready for my close-up,” and, “I am big… It’s the pictures that got small”—have become immortalized in popular culture, sometimes at the risk of ignoring the Herculean film they are attached to. But when unpeeled for all their significance, they suggest everything that’s so moving, mysterious, and timeless about one of Wilder’s very best films. Uttered by Norma Desmond (portrayed in an iconic performance by Gloria Swanson), the aging, increasingly obsolete thespian at the core of the story, the words sound simultaneously irrelevant and immediate, seductive and aggressive, wistful and triumphant, all paradoxes that Wilder’s film effortlessly radiates. A spirited dismantling of the image-obsessed, fame-lusting Hollywood film industry that is itself drunk on the stately rhythms of classical Hollywood, Sunset Boulevard speaks to the inherent contradictions of American film culture with unmatched poignancy. (Carson Lund)

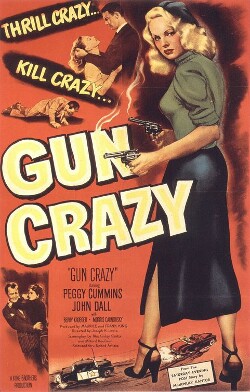

- Gun Crazy (1950, Joseph H. Lewis)

Femmes don’t get much more fatale than Peggy Cummins’ psychotic sharpshooter in Joseph H. Lewis’ Gun Crazy. Like Nightmare Alley, this story begins in a sideshow carnival, though the dark crimes that follow are far less subtle than the sophisticated confidence game which that earlier film evoked. Cummins’ Annie Starr seduces fellow deadshot Bart Tate (John Dall), then coaxes him into an ongoing series of holdups and robberies, each seemingly more violent than the last. The film predates Bonnie and Clyde by almost two decades, but with an extra layer of gonzo: Starr’s obvious sexual arousal at the gunplay is par for the course in this kind of piece, but not the actress’s mesmerizing portrayal of a fundamentally unhinged mind. She speaks volumes with quietly widening eyes, pursed lips, and whispered promises she has no intention of keeping. When the violence explodes, we share her exhilaration, though unlike her, our queasy understanding of the costs involved leave no doubt as to where this particular joy ride will end. (Rob Vaux)