Most film historians say that “film noir” is a cinematic movement that began in 1940 with Boris Ingster’s little-seen film “Stranger on the Third Floor” (staring Peter Lorre) and ended in 1958 with Orson Welles’s “Touch of Evil.” The roughly 300 films released during this period that make up the genre share a sensibility of narrative, political, stylistic, thematic, and visual elements. French film theorists originally coined the term in 1946 to describe a group of films that included “The Maltese Falcon” (1941), “Double Indemnity” (1944), and “Laura” (1944). Though an American phenomenon, many of Noir’s filmmakers hailed from throughout Eastern and Western Europe – many on the run from fascism. Little did they know that right-wing extremism would follow them across the ocean to America’s social and political stage.

Most film historians say that “film noir” is a cinematic movement that began in 1940 with Boris Ingster’s little-seen film “Stranger on the Third Floor” (staring Peter Lorre) and ended in 1958 with Orson Welles’s “Touch of Evil.” The roughly 300 films released during this period that make up the genre share a sensibility of narrative, political, stylistic, thematic, and visual elements. French film theorists originally coined the term in 1946 to describe a group of films that included “The Maltese Falcon” (1941), “Double Indemnity” (1944), and “Laura” (1944). Though an American phenomenon, many of Noir’s filmmakers hailed from throughout Eastern and Western Europe – many on the run from fascism. Little did they know that right-wing extremism would follow them across the ocean to America’s social and political stage.

A moody cynicism about the scales of justice and America’s flawed postwar capitalist system are running themes. These reflect an America recovering from the Great Depression, only to emerge in World War II, which gave way to the Cold War. The archetypical American Dream of the ‘50s is not part of the Noir equation. Noir’s alienated characters are naturally distrustful, seen-it-all, people out to salvage what they can from a ruthless society. They fight dirty. They’re survivors — but they jealously guard their individuality. Death is always just around the corner for characters ready to go out with their sex drive, dignity, intellect, wit, and stylish charm intact. Guns, cigarettes, booze, and sleazy hotel rooms — many of the scripts were adapted from pulp fiction magazines — come with the territory.

As its name implies, the visual aspects of film noir emphasize the high contrast between the black and white extremes of the film stock used predominantly during the period. German Expressionist cinema (reference “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” – 1923) was influential on cinematographers attempting to capture a dislocated sense of social isolation that defined characters whose motivations are often centered around their need to escape.

Significant too is the “pulp” literary tradition, which gave noir its grittiness with an underworld environment in a country whose repressive influences are always lurking in the shadows. Such shadows allowed noir filmmakers to play with a built-in image system of white light penetrating into claustrophobic interior and exterior spaces. Writers such as Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Kames M. Cain, and Cornell Woolrich provided a “hard-boiled” template for plot and dialogue that Noir filmmakers mined for every bit of narrative gold they could.

The advent of the Kodak Eastman Color process in 1952 contributed to the ultimate demise of film noir, though not all Classic Film Noirs were filmed in black and white. Kodak provided a quicker and more economic alternative to the Technicolor system that had been used as far back to the 1920s for such high-budget films such as “The Wizard of Oz” and “Gone With the Wind” (1939).

Politically, the demise of Film Noir can be traced back to Senator Joseph McCarthy’s House on Un-American Activities Committee, whose witch-trials resulted in the blacklisting many of the screenwriters, actors, and directors responsible for keeping Film Noir going. Noir filmmakers such as Edward Dmytryk (“Crossfire” – 1947) and John Berry (“He Ran All the Way” 1951) were exiled from making films in America along with other members of the “Hollywood Ten,” whose creative potentials were cut short by the same repressive cultural and economic system they had so fiercely commented on. (Introduction written by Cole Smithey)

After the jump, is the third part of our list, ranks 21 to 30. Tomorrow, we’ll present 11 to 20.

Ranked List, Part 3

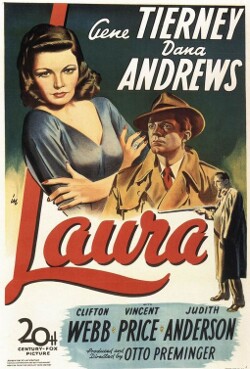

- Laura (1944, Otto Preminger)

Though Gilda might beg to differ, “Laura” is the most famous name in noir history, and the one that inspired its most noted musical theme. With the invaluable aid of Joseph LaShelle’s Oscar-winning camerawork, Otto Preminger’s directorial debut reveals the demimonde of New York as a snake pit, writhing with relentless ladder climbing, obsession, and murder, further tinged with necrophilia as coarse detective Dana Andrews, investigating the murder of the heart-stopping lady of the title (Gene Tierney), falls in love with her via her letters, diary, and portrait. “Love is eternal. It has been the strongest motivation for human actions throughout history,” notes columnist Waldo Lydecker (Clifton Webb), Laura’s BFF, controlling and controlled. “Love is stronger than life. It reaches beyond the dark shadow of death.” He and Preminger, at the beginning of a noir-flecked career, received Oscar nominations for this exquisite leap into the dark. (Robert Cashill)

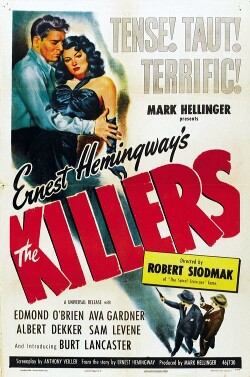

- The Killers (1946, Robert Siodmak)

The opening of The Killers may be the most perfect literary adaptation in all of cinema. The scenes of the two hitmen holding a small-town diner hostage until someone goes and gets them their mark uses practically every word of Ernest Hemingway’s short story of the same name. What’s amazing about Robert Siodmak’s 1946 thriller is that everything that happens after has been completely invented by screenwriter Anthony Veiller (who also wrote Orson Welles’ The Stranger). Whereas Hemingway gave his readers no backstory, Veiller’s script is nothing but backstory, detailing all the events that drove Burt Lancaster’s Swede to hide out in the middle of nowhere in order to avoid getting pumped full of lead. As with much of noir, the worst crimes are those of the heart. In this case, a fellow should have never fallen for a girl like Ava Gardner. Not unless he wanted to die for her. (Jamie S. Rich)

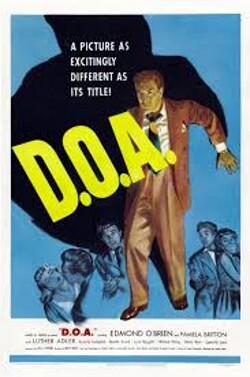

- D.O.A. (1950, Rudolph Maté)

A man walks into a homicide detective’s office. “I want to report a murder,” he says. “Who was murdered?” asks the detective. “I was.” One of the great “grabber” openings in movie history lives up to its promise, introducing a tense thriller about a poisoned accountant with days to live tracking down his own killer. Doomed Frank is an ordinary sinner, but D.O.A.’s Protestant fatalism is revealed as he’s punished most harshly just when he decides to clean up his act. This overachieving B-picture is anchored by a tough performance by Edmund O’Brien, who goes from would-be cad to living ghost to hero, and a twisty script that delivers on the shifty villains, sadistic heavies and deceitful dames. (Gregory J. Smalley)

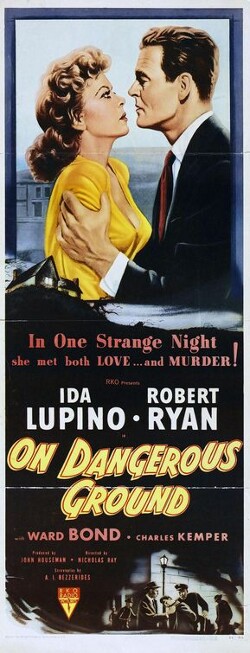

- On Dangerous Ground (1952, Nicholas Ray)

It’s an unusual noir that spends most of its time in the mountains, but that’s where Robert Ryan’s cop, Jim Wilson, finds himself after taking some time away from the infectious corruption of the city. A girl’s murder draws Wilson into conflict with her grief-stricken father (Ward Bond) and the blind sister (Ida Lupino) of the mentally challenged murder suspect. Director Nicholas Ray and screenwriter A.I. Bezzerides depict Wilson in sharp relief to both the victim’s morally compromised father and the suspect’s soulful sister in order to illustrate the complexity of the transgressive nature of crime on all involved. (Tony Dayoub)

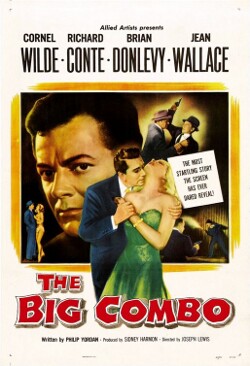

- The Big Combo (1955, Joseph H. Lewis)

Cornel Wilde’s acerbic, broken detective is the leader of a whole carnival of some of the most bitter people ever to populate a low-rent, seedy crime story: the snarling gangster’s girlfriend played by Jean Wallace, the charismatic but openly nihilistic gangster himself, embodied with sharklike intensity by Richard Conte, a pair of miserable, contemptible gay lovers/assassins, and plenty more serve to make The Big Combo one of the morally darkest of all noirs, and that’s without taking into account John Alton’s intensely dark cinematography, suffocating the life out of every scene with ponderous blackness. It’s a triumphantly well-mounted plunge into the very nastiest depths the genre had to offer with style and fearlessness, and its depiction of a world stripped of even the most basic decency is as potent and pulverizing as anything else in noir. (Tim Baytton)

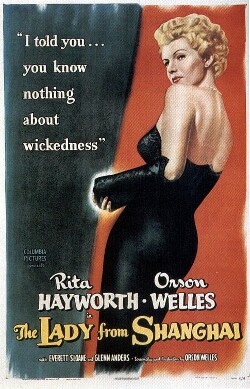

- The Lady from Shanghai (1947, Orson Welles)

Film noir gets a bad rap for being misogynistic, but the truth is that the women of noir just refuse to be trapped in a dull box as role models of soft femininity. The women of noir—no matter how bad or how evil—were a deliciously fascinating lot. They operated in a man’s world and used sex to get what they wanted. One of the best femme fatales of the genre is Rita Hayworth in The Lady From Shanghai: gorgeous, sensuous, irresistible, and nothing but trouble. With her bleached bob, Hayworth (then married to director Orson Welles) looked like an angel but was wicked at the core. Her only defense is that “those who follow their nature keep their original nature in the end,” and when she looked at you with those sultry eyes you bought it wholeheartedly. Hayworth’s performance and Welles’ intoxicatingly stylized direction make this film memorable. (Beth Accomando)

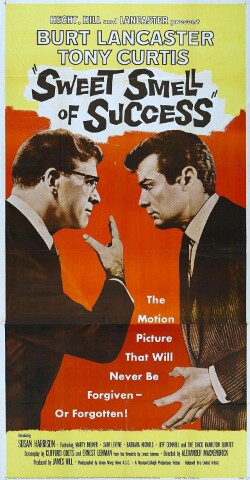

- Sweet Smell of Success (1957, Alexander Mackendrick)

“Match me, Sidney.” “The cat’s in a bag and the bag’s in a river.” “You’re dead, son. Get yourself buried.” Playwright Clifford Odets, who skewered Hollywood with The Big Knife, tears into New York’s tabloid scene one quotable line at a time with one of the tangiest screenplays ever written. Bringing his words to vivid life are Burt Lancaster, as J.J. Hunsecker, the columnist at the top of his game, and Tony Curtis, as press agent Sidney Falco, who from the lower rungs brings him the red meat for his exclusives. Seat-of-the-pants filming in Times Square locales by director Alexander Mackendrick and cinematographer James Wong Howe, and Elmer Bernstein’s hot jazz score, add to the verisimilitude, as Odets cranked out rewrites throughout the shoot. Underappreciated in its day, the film has grown in cult fascination, with a character in 1982’s Diner quoting it throughout. “I love this dirty town,” says Hunsecker, and so too have audiences come to embrace this gem. (Robert Cashill)

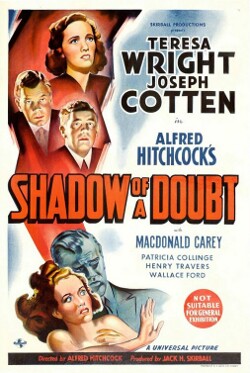

- Shadow of a Doubt (1943, Alfred Hitchcock)

In 1943, when war and propaganda films competed with musicals and other feel good fare, Alfred Hitchcock released a masterpiece that, like David Lynch’s “Blue Velvet” would decades later, peered beneath the facade of the perfect, sleepy little American town. That Our Town‘s Thornton Wilder had a hand in an early draft of the script is a delicious irony. Teresa Wright plays Charlie, the older of two sisters living an unremarkable middle-class life in Santa Rosa, California. She’s elated when the man she’s named after, her mother’s brother, wires to announce he’s coming for a visit. Shortly thereafter, two men ostensibly profiling the ‘all American family’ arrive; one of them tells Charlie they suspect her uncle may be the serial killer known as the Merry Widow Murderer. This is a film noir that is equal parts light and dark, each represented by one of the Charlies. Soon, the ‘perfect’ little town rolls over and shows its underbelly. Shadow of a Doubt was Hitchcock’s favorite of his own films. Its duality runs deep. (Laura Clifford)

- Nightmare Alley (1947, Edmund Goulding)

There’s something about a carnival that fits right in with the seedy world of noir. Cheap hustlers, cheaper sex and the shopworn dreams of easy money that vanish right before your eyes: carnivals are a breeding ground for petty schemes and tarnished souls. Nightmare Alley delivered a great one in the form of Tyrone Power, a classic leading man who bought the rights to the story solely so he could act against type. He plays the third-rate con artist Stanton Carlisle, who latches onto a husband-and-wife mentalist act: a couple carrying a fool-proof code to give the impression of extraordinary mental powers. Murder, mayhem, and infidelity follow, such that even the tacked-on happy ending—seemingly made over the director’s active protests—cannot blunt their grim power. Nightmare Alley stands up in part because of its comparatively high production values (unusual for noir at the time), but mainly because it profoundly understands the genre’s cold, black heart. Even today, its darker moments send chills down the spine, and its rise-and-fall story paints a profoundly unsettling picture of the American Dream at its bleakest. (Rob Vaux)

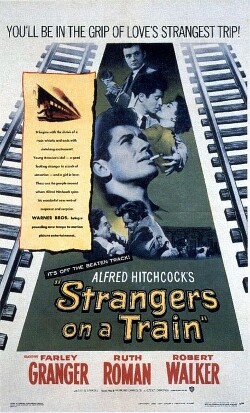

- Strangers on a Train (1951, Alfred Hitchcock)

Strangers on a Train, based on the novel by Patricia Highsmith, is the story of a tennis champion with the everyman name of Guy (Farley Granger) who meets a fan named Bruno (Robert Walker) on a train. Bruno is more than a fan; nowadays, we might call him a stalker. He seems to know all about Guy, including a messy situation with Guy’s wife, who is unfaithful but refuses to give him a divorce. Bruno tells Guy about his own problems with his father and proposes that they swap murders: there will be no ties between the perpetrator and the victim and so no one will suspect them. Hitchcock uses shots of crisscrossing train tracks and walking feet to establish a sense of urgency and intersection. Themes of duality are subtly reinforced visually throughout the film, aided by the casting. In addition to his usual cameo appearance in a cameo on screen, Hitchcock’s own daughter appears in the film; she is similar in appearance to Guy’s wife, triggering an emotional reaction in the unstable Bruno. In a powerfully unsettling moment, an entire arena watches Guy’s tennis game, heads turning back and forth in unison, as Bruno stares fixedly, unblinkingly, piercingly, at Guy. (Nell Minow)

- Force of Evil (1948, Abraham Polonsky)

The blunt, fraternal New York tragedy Force of Evil would resound as a proto-Scorsese film even if Marty hadn’t owned up to it. “All that Cain did to Abel was murder him,” snarls Leo Morse (Thomas Gomez), angst-ridden operator of a small-time “numbers bank,” at younger sibling Joe (John Garfield), a racketeer’s lawyer, as they conduct a mortal battle over their future. While Joe pressures Leo into accepting the snakelike grip of “the Combination” in a scheme to make the numbers game a legal, mob-skimmed lottery, the urban male universe quakes until it threatens to collapse in a round-robin of betrayal. Director Abraham Polonsky, a future blacklistee, plants his scenario with images of institutional rot, and Joe sighs over Leo’s defiant refusal to move up the chain of exploitation: “To get your pleasure from not taking… Just to live and be guilty?” (Bill Weber)