Most film historians say that “film noir” is a cinematic movement that began in 1940 with Boris Ingster’s little-seen film “Stranger on the Third Floor” (staring Peter Lorre) and ended in 1958 with Orson Welles’s “Touch of Evil.” The roughly 300 films released during this period that make up the genre share a sensibility of narrative, political, stylistic, thematic, and visual elements. French film theorists originally coined the term in 1946 to describe a group of films that included “The Maltese Falcon” (1941), “Double Indemnity” (1944), and “Laura” (1944). Though an American phenomenon, many of Noir’s filmmakers hailed from throughout Eastern and Western Europe – many on the run from fascism. Little did they know that right-wing extremism would follow them across the ocean to America’s social and political stage.

Most film historians say that “film noir” is a cinematic movement that began in 1940 with Boris Ingster’s little-seen film “Stranger on the Third Floor” (staring Peter Lorre) and ended in 1958 with Orson Welles’s “Touch of Evil.” The roughly 300 films released during this period that make up the genre share a sensibility of narrative, political, stylistic, thematic, and visual elements. French film theorists originally coined the term in 1946 to describe a group of films that included “The Maltese Falcon” (1941), “Double Indemnity” (1944), and “Laura” (1944). Though an American phenomenon, many of Noir’s filmmakers hailed from throughout Eastern and Western Europe – many on the run from fascism. Little did they know that right-wing extremism would follow them across the ocean to America’s social and political stage.

A moody cynicism about the scales of justice and America’s flawed postwar capitalist system are running themes. These reflect an America recovering from the Great Depression, only to emerge in World War II, which gave way to the Cold War. The archetypical American Dream of the ‘50s is not part of the Noir equation. Noir’s alienated characters are naturally distrustful, seen-it-all, people out to salvage what they can from a ruthless society. They fight dirty. They’re survivors — but they jealously guard their individuality. Death is always just around the corner for characters ready to go out with their sex drive, dignity, intellect, wit, and stylish charm intact. Guns, cigarettes, booze, and sleazy hotel rooms — many of the scripts were adapted from pulp fiction magazines — come with the territory.

As its name implies, the visual aspects of film noir emphasize the high contrast between the black and white extremes of the film stock used predominantly during the period. German Expressionist cinema (reference “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” – 1923) was influential on cinematographers attempting to capture a dislocated sense of social isolation that defined characters whose motivations are often centered around their need to escape.

Significant too is the “pulp” literary tradition, which gave noir its grittiness with an underworld environment in a country whose repressive influences are always lurking in the shadows. Such shadows allowed noir filmmakers to play with a built-in image system of white light penetrating into claustrophobic interior and exterior spaces. Writers such as Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Kames M. Cain, and Cornell Woolrich provided a “hard-boiled” template for plot and dialogue that Noir filmmakers mined for every bit of narrative gold they could.

The advent of the Kodak Eastman Color process in 1952 contributed to the ultimate demise of film noir, though not all Classic Film Noirs were filmed in black and white. Kodak provided a quicker and more economic alternative to the Technicolor system that had been used as far back to the 1920s for such high-budget films such as “The Wizard of Oz” and “Gone With the Wind” (1939).

Politically, the demise of Film Noir can be traced back to Senator Joseph McCarthy’s House on Un-American Activities Committee, whose witch-trials resulted in the blacklisting many of the screenwriters, actors, and directors responsible for keeping Film Noir going. Noir filmmakers such as Edward Dmytryk (“Crossfire” – 1947) and John Berry (“He Ran All the Way” 1951) were exiled from making films in America along with other members of the “Hollywood Ten,” whose creative potentials were cut short by the same repressive cultural and economic system they had so fiercely commented on. (Introduction written by Cole Smithey)

After the jump, is the second part of our list, ranks 31 to 39. Tomorrow, we’ll present 21 to 30.

Ranked List, Part 2

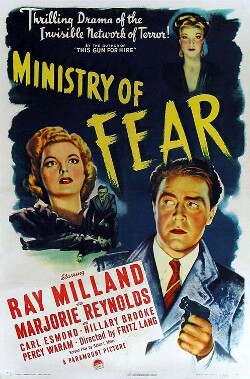

- Ministry of Fear (1944, Fritz Lang)

Fritz Lang’s Hollywood-era work was often a miraculous fusion of the director’s innate optimism with the indelible cynicism brought on by the rise of Nazi Germany and the United States’ own red scare, and his 1944 adaptation of Graham Greene’s novel was no exception. A seemingly innocent cake sets a plot into motion that covers the gamut of noirish elements—romance, betrayal, murder, and the persecution of the innocent—but the film’s heartbreaking moral inquiry is already well underway when the audience first meets protagonist Stephen Neale (Ray Milland), who is concluding his sentence for the attempted mercy killing of his sickly wife. Lang’s masterful direction makes Ministry of Fear as entertaining an entry as the genre ever saw, breathless right up until its no-way-out climax, while the hilarious closing shot suggests an audience’s collective sigh of relief. (Rob Humanick)

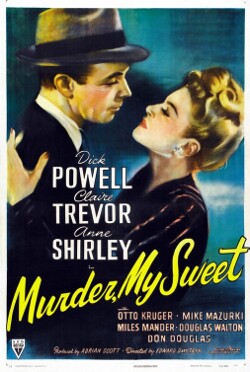

- Murder, My Sweet (1944, Edward Dmytryk)

Aging musical star and matinee idol Dick Powell wasn’t anyone’s first choice to play a hard-boiled Raymond Chandler anti-hero, but in 1944 he forced people to change their minds. He insisted on being cast in a straight dramatic role before doing any musicals for RKO. The role he got was Philip Marlowe in Murder, My Sweet (the novel was called Farewell My Lovely, but that sounded too much like one of Powell’s musicals, so the name was changed). The trailers promised Powell in “an amazing new type of role,” and they were right. Powell, not hiding his age and letting a five o’clock shadow darken his pretty-boy looks, proved he could crack wise and deliver the goods as a noir gumshoe. The film was grittily directed by Edward Dmytryk, with a sexy Claire Trevor on hand to generate some heat. (Beth Accomando)

- (tie) The Asphalt Jungle (1950, John Huston)

Director John Huston set a high standard with The Asphalt Jungle, and one that remains a template for modern crime films: the ‘heist gone wrong’ picture. It might not have been the first film to feature a brilliant crime come apart due to greed and unforeseen events, but films like Reservoir Dogs owe much to this work. John Huston uses visual cues to show that the world of The Asphalt Jungle is a dying one; from the opening shots of a lonely man skulking in a city virtually in ruins to the juxtaposition of death bathed in light, the film tells us so much with just the imagery. However, Huston could also craft a film where dialogue tells us more with its subtext. “One way or another, we all work for our vices,” one character says. This might well be the theme of not just The Asphalt Jungle, but all film noir. The film also features Marilyn Monroe in her first important role, before her legend blinded people to her genuine acting ability. A brilliant film noir, The Asphalt Jungle’s dark story with sympathetic criminals (and their dames) set a high standard for noir films where the criminals, not the crime, was the focus. (Rick Aragon)

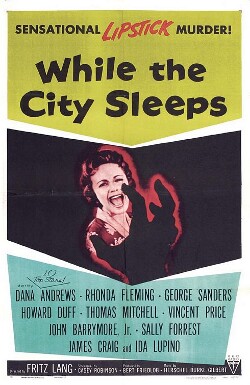

- (tie) While the City Sleeps (1956, Fritz Lang)

The serial killer plot that drives While the City Sleeps serves as a mere pretext for Lang’s fascination-repulsion with the news media, just as, in some ways, the plight of the child-murderer Hans Beckert in M was but a pretext for the remarkable dissection of Berlin’s nocturnal landscape. Although he’d arguably been the oracle whose previsions of TV and video appeared in his films long before they became a reality, Lang’s While the City Sleeps treats contemporary media delivery—the wire, the tube, and by implication, the internet and the smart-phone—as the freakish apparatus of some alien interloper. Far from serving the public good, the men and women of the press have become just another kind of pusher, generating and proliferating cancerous data that informs little, and only seems to contaminate the air, the light, and the empty spaces. Lang’s gliding camera, pushing in on screamers, downward on meddling hands, and around swiveling torsos, brings a kind of paradoxical vitality to a world of scoundrels that the director would seem, with a patriarchal scowl, to condemn with a glance and a haughty sniff. (Jamie N. Christley)

- Rififi (1955, Jules Dassin)

From the incomparable Jules Dassin comes arguably one of the most underrated gems in film noir, Rififi. Following the story of four ex-cons trying to take on one last heist, this film may sound like the inspiration for hundreds of subsequent pictures, but with breakneck pacing and a director at the very top of his game, this is more than just a genre curio. Featuring one of the most breathtaking sequences in all of classic noir, this picture from the blacklisted auteur Jules Dassin may be one that has flown under the radar all of these years, but for noir hounds, it’s one of the greatest examples of what the genre can do both structurally and aesthetically, becoming a definitive entry in the canon. (Joshua Brunsting)

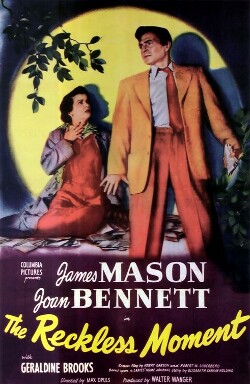

- The Reckless Moment (1949, Max Ophüls)

Set in post-war suburbia, Max Ophuls’ American masterpiece combines crime drama and what Hollywood once called a “women’s picture” for a portrait of American middle class security colliding with big city corruption. One-time noir femme fatale Joan Bennett is the wife and mother protecting her daughter from a blackmailer (a darkly attractive and quietly menacing James Mason). The continental Ophuls moves the camera with his usual grace, tracking and panning and tilting with the action, to capture the busy-ness and bustle of American life in the sunny suburbs, the shadowy city, and the family home. But beyond the crime thriller conventions, the film limns the social prison of the middle class family, revealing how powerless Bennett finds herself in this society as she attempts to secure a loan or to get money without a husband at her side. (Sean Axmaker)

- Scarlet Street (1945, Fritz Lang)

Scarlet Street is a strange film from Fritz Lang, who saw the world in bold, dark terms. His films are outsized and arguably none better personifies that than his 1945 masterwork, featuring a grand performance by Edward G. Robinson as Chris Cross, a man so meek that he is almost invisible. He has a functional job and is married to a shrewish nag who makes him work on his paintings in the bathroom. One night he meets Kitty, whom he falls in love with, although we can see that she’s no good. Kitty hatches a plan to dupe Chris out of his money through his art, but she isn’t smart enough to see that he isn’t a great painter. Chris soon finds himself drawn to things he wouldn’t do otherwise. The movie never takes the turn that we expect, but it’s not hard to figure out that it won’t end well. (Jerry Goran)

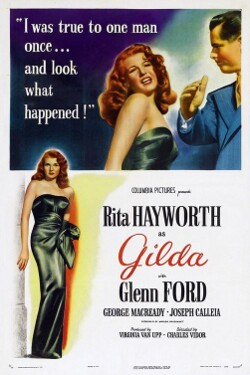

- Gilda (1946, Charles Vidor)

Of all the notable entrances in film noir, Rita Hayworth’s arrival onscreen in Charles Vidor’s Gilda is an easy frontrunner for most unforgettable. “Gilda, are you decent?” her husband asks, and in response, Hayworth appears from the bottom of the screen, tossing her flame-red hair (evident even in black-and-white), letting loose with a coy grin. “Me?” she says. “Sure. I’m decent.”

Of course, she’s anything but, and Vidor’s film is devoted to telling us just how indecent this femme fatale really is. Men kill each other for the privilege of being wrapped around her finger. Glenn Ford makes for the perfect foil: he’s stiff and a bit dopey, and you know from the start he can never handle what’s coming. The fun is in watching just how tangled everything becomes. (Jamie S. Rich)

- The Prowler (1951, Joseph Losey)

Joseph Losey’s 1951 thriller, pseudonymously co-written by Dalton Trumbo, is nearly a perfect film noir. Van Heflin plays a cop who, after responding to a call that a woman (Evelyn Keyes) spotted a peeping tom outsider her window, falls in love with the woman in question. Away though her husband may be most evenings, his voice comes through (sometimes eerily) loud and clear over their living room radio. His nightly sign-off, “I’ll be seeing you, Susan,” quickly turns from endearing to overbearing, until she and especially her one-time rescuer just can’t stand it anymore.

The forbidden affair is a common trait of film noir, but Losey’s depiction is quite unique in its truly sordid, lurid nature, as though the lead characters come to be soaked in their own sin and degradation. Taut suspense, nightmarish atmosphere, and depravity: The Prowler is crime fiction at its finest. (Scott Nye)