Most film historians say that “film noir” is a cinematic movement that began in 1940 with Boris Ingster’s little-seen film “Stranger on the Third Floor” (staring Peter Lorre) and ended in 1958 with Orson Welles’s “Touch of Evil.” The roughly 300 films released during this period that make up the genre share a sensibility of narrative, political, stylistic, thematic, and visual elements. French film theorists originally coined the term in 1946 to describe a group of films that included “The Maltese Falcon” (1941), “Double Indemnity” (1944), and “Laura” (1944). Though an American phenomenon, many of Noir’s filmmakers hailed from throughout Eastern and Western Europe – many on the run from fascism. Little did they know that right-wing extremism would follow them across the ocean to America’s social and political stage.

Most film historians say that “film noir” is a cinematic movement that began in 1940 with Boris Ingster’s little-seen film “Stranger on the Third Floor” (staring Peter Lorre) and ended in 1958 with Orson Welles’s “Touch of Evil.” The roughly 300 films released during this period that make up the genre share a sensibility of narrative, political, stylistic, thematic, and visual elements. French film theorists originally coined the term in 1946 to describe a group of films that included “The Maltese Falcon” (1941), “Double Indemnity” (1944), and “Laura” (1944). Though an American phenomenon, many of Noir’s filmmakers hailed from throughout Eastern and Western Europe – many on the run from fascism. Little did they know that right-wing extremism would follow them across the ocean to America’s social and political stage.

A moody cynicism about the scales of justice and America’s flawed postwar capitalist system are running themes. These reflect an America recovering from the Great Depression, only to emerge in World War II, which gave way to the Cold War. The archetypical American Dream of the ‘50s is not part of the Noir equation. Noir’s alienated characters are naturally distrustful, seen-it-all, people out to salvage what they can from a ruthless society. They fight dirty. They’re survivors — but they jealously guard their individuality. Death is always just around the corner for characters ready to go out with their sex drive, dignity, intellect, wit, and stylish charm intact. Guns, cigarettes, booze, and sleazy hotel rooms — many of the scripts were adapted from pulp fiction magazines — come with the territory.

As its name implies, the visual aspects of film noir emphasize the high contrast between the black and white extremes of the film stock used predominantly during the period. German Expressionist cinema (reference “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” – 1923) was influential on cinematographers attempting to capture a dislocated sense of social isolation that defined characters whose motivations are often centered around their need to escape.

Significant too is the “pulp” literary tradition, which gave noir its grittiness with an underworld environment in a country whose repressive influences are always lurking in the shadows. Such shadows allowed noir filmmakers to play with a built-in image system of white light penetrating into claustrophobic interior and exterior spaces. Writers such as Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Kames M. Cain, and Cornell Woolrich provided a “hard-boiled” template for plot and dialogue that Noir filmmakers mined for every bit of narrative gold they could.

The advent of the Kodak Eastman Color process in 1952 contributed to the ultimate demise of film noir, though not all Classic Film Noirs were filmed in black and white. Kodak provided a quicker and more economic alternative to the Technicolor system that had been used as far back to the 1920s for such high-budget films such as “The Wizard of Oz” and “Gone With the Wind” (1939).

Politically, the demise of Film Noir can be traced back to Senator Joseph McCarthy’s House on Un-American Activities Committee, whose witch-trials resulted in the blacklisting many of the screenwriters, actors, and directors responsible for keeping Film Noir going. Noir filmmakers such as Edward Dmytryk (“Crossfire” – 1947) and John Berry (“He Ran All the Way” 1951) were exiled from making films in America along with other members of the “Hollywood Ten,” whose creative potentials were cut short by the same repressive cultural and economic system they had so fiercely commented on. (Introduction written by Cole Smithey)

After the jump, is the first part of our list, ranks 40 to 50 along with two honorable mentions that fell just short of the top 50 along.Tomorrow, we’ll present 31 to 39.

Honorable Mentions

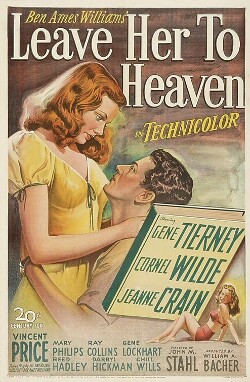

Leave Her to Heaven (1945, John M. Stahl)

Leave Her to Heaven (1945, John M. Stahl)

John M. Stahl’s Leave Her to Heaven is not your typical film noir; it’s not only in color, but Technicolor. It also fails to fit the standard mold of a man being led deeper and deeper into the compromise of his moral center by an unscrupulous, opportunistic and beautiful woman. As the film begins, though, it seems set to follow that path. We meet a man who has just been released from prison and he begins to tell his story, which begins with meeting a gorgeous woman. As the telling progresses, however, we spend much more time with the femme fatale (Gene Tierney)

than with the ostensible protagonist (Cornel Wilde)

and it becomes clear that there’s an irony to Stahl’s use of brilliant Technicolor hues; it’s a reminder that the term “noir” applies not to a film’s palette but to its themes. Leave Her to Heaven goes to places more blatantly and vividly disturbing than the average crime film of the era, and that queasy effect is enhanced by Leon Shamroy’s cinematography, for which he won an Academy Award. Most of the great films noir used their female characters as symbols of the low temptations that can corrupt a man’s soul. Leave Her to Heaven stands out because it brings us face to face with a woman whose soul may be well beyond repair to begin with. (David Bax)

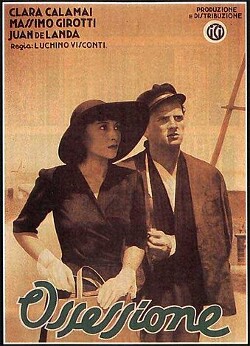

Obsession (1943, Luchino Visconti)

Obsession (1943, Luchino Visconti)

Luchino Visconti’s first film, Obsession is loosely based on J.M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, but because the production company never had the rights to adapt the novel, the film was largely unseen for decades. A genre story of ill-fated love, murder and betrayal., Obsession is considered by some to be the first neorealist film and the only Italian noir. While Visconti had been influenced by French poetic realism and melodramatic styles, his description of the Italian province and the small world of his characters seems to anticipate subsequent films from De Sica, Rossellini, and De Santis. Shot in WWII occupied Italy, the film also had a clear political intent, staging the contradictions and frailty of the bourgeois family—the cornerstone of fascist propaganda. The presence of a covert homosexual character made the film even more intolerable to the authorities, but Visconti was able to steal the original negative, saving the movie that would have otherwise seen only a very fragmented distribution wartime distribution. (Marco Albanese)

Ranked List, Part 1

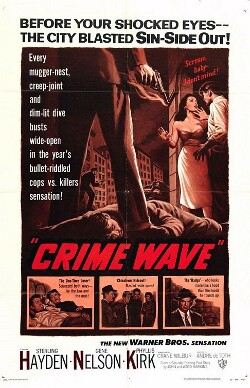

- (tie) Crime Wave (1954, André De Toth)

It takes an outsider to see the strangeness of Los Angeles at night, and Hungarian André De Toth displays in this shoestring 1954 masterpiece an unerring feel for the ominous gradations of highways, roadside cafés, and shabby apartments. Following a botched gas station holdup, fugitives hole up at the home of a former San Quentin cellmate (Gene Nelson), who knows all too well the plight of the marked civilian: “Once you’ve done a bit, nobody leaves you alone.” If the underworld is slashed by deep shadows, the police station is a blanched, echoing cosmos in which the detective (Sterling Hayden)

looms over suspects like an unforgiving, toothpick-chewing god. Ruthlessly unsentimental yet bleakly humanistic, De Toth’s hard-edged gem casts a beady eye on the inescapable violence and fragility of connection of the noir world. (Fernando F. Croce)

- (tie) Murder By Contract (1958, Irving Lerner)

Irving Lerner’s Murder by Contract is a gritty depiction of a handsome man, Claude (Vince Edwards), who makes a career move from an honest but poorly paid wage-earner to becoming a high-paid contract killer. He considers his work a business decision—instead of “price cutting” he does throat-cutting, and while the risk is high, so is the profit. This beautiful, neglected low-budget film noir is an absolutely superb thriller, reminiscent of Jean-Pierre Melville’s great existentialist character study Le Samurai, in thatthe film remains less fixed on the story and more on how the protagonist is suave and calculatingly dispassionate. The lack of contrivances and naturalist performances only add to its power. Interestingly enough, the director and screenwriter never went on to do something even close to the quality this B film achieved, while this role catapulted Vince Edwards’ career into deserved stardom. Martin Scorsese said this was the film that influenced him most when he made Mean Streets. (Dennis Schwartz)

- (tie) Man Hunt (1941, Fritz Lang)

I first encountered Man Hunt when network television acted as a sort of cinematheque for budding cinephiles. The film was already in progress; what stayed in my mind was John Carradine chashing Walter Pidgeon through the underground train tracks. Carradine gets electrocuted in what is arguably the most famous scene in the film. As it turned out, that scene is straight from Geoffrey Household’s novel, Rogue Male, although much of the narrative, especially the scenes involving Joan Bennett, are the invention of screenwriter Dudley Nichols. The other major change is that the “big game” that literally triggers the rest of the story is very clearly Adolf Hitler. (Keep in mind that novel was published in 1939, while the film was released in June 1941, half a year before the U.S. declaration of war against Germany.)

Railroad tracks would play a part in other films by Fritz Lang, and Man Hunt was also the first of Lang’s four films with his muse Joan Bennet. The film was an assignment, passed over reportedly by John Ford. Fortunately, the job was done by the filmmaker most personally aware of the Nazi threat. (Peter Nellhaus)

- (tie) The Spiral Staircase (1945, Robert Siodmak)

In between vintage noir efforts like Phantom Lady and The Killers, director Robert Siodmak helmed this creepy period piece that melds his flair for shadowy noir with “old dark house” horror-suspense elements. The story of a mute woman stalked by a fetishist serial killer preying on handicapped women is startlingly edgy, as is the stylish cinematography of Nicholas Musuraca, evidenced in an opening scene that finds a lone, unblinking eye peering from a closet at the latest prey. It’s a chilling moment that anticipates landmark genre tales of obsession ranging from Psycho and Peeping Tom to Black Christmas and The Silence of the Lambs. (Mark H. Harris)

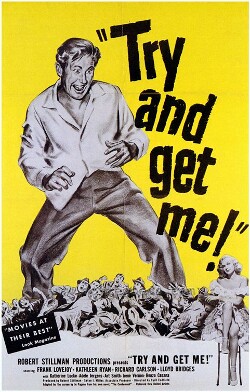

- The Sound of Fury aka Try and Get Me (1950, Cy Endfield)

The 1936 Fritz Lang film Fury is the more famous of the two films based on a murder that took place in San Jose, California in the 1930s, but Cy Endfield’s 1950 version, The Sound of Fury (aka Try and Get Me!)

is the more accurate and unsparing. Lloyd Bridges and Frank Lovejoy are superb as the partners in crime whose fates are sealed by sensational coverage by a publisher trying to sell newspapers. Endfield’s direction, in his last major American film before the Communist witch hunt of the 1950s forced him into exile in England, offers a nihilistic vision of group-think and the court of public opinion that was not destined to find favor in its own time. Looking at the film now, it seems timeless in the brutality of its psychology, making the haves of society seem decadent and profit-driven, and showing how desperation and lack of opportunity can turn the luckless into criminals. (Marilyn Ferdinand)

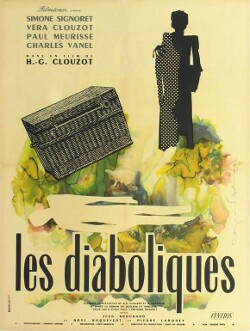

- (tie) Diabolique (1955, Henri-Georges Clouzot)

This refreshingly female-driven French noir classic incorporates healthy doses of mystery, horror, psychological thriller and police procedural in its undulating tale of a plot hatched by two teachers at a boarding school to kill the headmaster—who, by the way, is married to one and is having an affair with the other. As the twists, back-stabs and double-crosses mount, it should come as no surprise to find out that the book upon which it’s based, Celle qui n’etait plus (She Who Was No More), was penned by the same writing team (Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac)

behind the novel that inspired Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo. If you sense any risqué lesbian overtones in the film, it’s not coincidental; the book featured two female lovers. (Mark H. Harris)

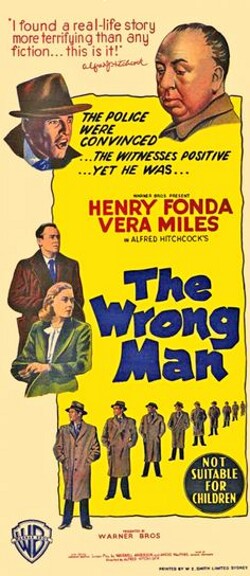

- (tie) The Wrong Man (1956, Alfred Hitchcock)

Though a riff on one of Alfred Hitchcock’s most regular themes, The Wrong Man represents a kind of quiet break for the director. Perhaps because it was based on a true story, Hitchcock pulls back on his stylistic trickery, instead going for a far more natural, straightforward shooting style. The simple black-and-white imagery plays to the strengths of the movie’s star, Henry Fonda, whose everyman persona adds a disturbing wrinkle to the drama. If he is guilty of the crime he’s accused of, then anyone we pass on the street might also be a killer. On the other hand, if he’s innocent, then couldn’t each and every one of us find ourselves in the same predicament? (Jamie S. Rich)

- The Naked City (1948, Jules Dassin)

Twelve years before Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless became an international sensation for its jazzy use of on-location photography in Paris, under-appreciated hired hand Jules Dassin was modestly treading the same territory in New York City. The result, 1948’s The Naked City, may not have been the very first American genre film to be shot on the streets, but it’s one of the most memorable of its kind. A rigorous police procedural located in cramped office rooms and on sun-bleached Manhattan pavement, the film occasionally suffers from one-dimensional characterizations, but it’s all of a piece with Dassin’s taut direction, which reaches an exhilarating climax in the thirty minute chase sequence that concludes the film, a marvel of tense pacing that still thrills today. (Carson Lund)

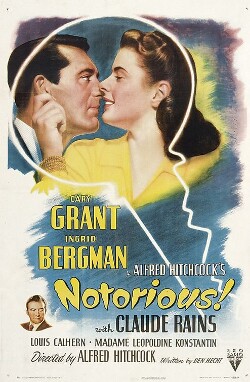

- (tie) Notorious (1946, Alfred Hitchcock)

Based on John Taintor Foote’s two-part short story “The Song of the Dragon” (which originally appearred in the 1921 Saturday Evening Post), Notorious is transformed into a compelling post World War II saga of betrayal resulting from the conflict between love and duty. An opening subtitle starts the film from Miami, Florida, Three-Twenty P.M., April the Twenty-Fourth, Nineteen Hundred and Forty-Six, but this is incidental. Nazis are the chosen enemy, but that’s only due to the timing of the film—a year later the foreign spies would be Russian communists; today, they might be Arab terrorists. Director Alfred Hitchcock crafts a definitive boom shot at the party with the camera gradually closing in on Bergman’s hand until the wine cellar key is shown. Other moments also stand out: the camera placement behind the mysterious “dark” stranger (Cary Grant)

at the Florida bungalow party, the blurry focus, Dutch angles and rotating point of view shots through which the hungover Bergman sees Grant, and the “longest kiss in screen history,” where a tight shot on Grant and Bergman lasts three minutes on one take without violating the three second limit on kissing imposed by the Hollywood code. (John A. Nesbit)

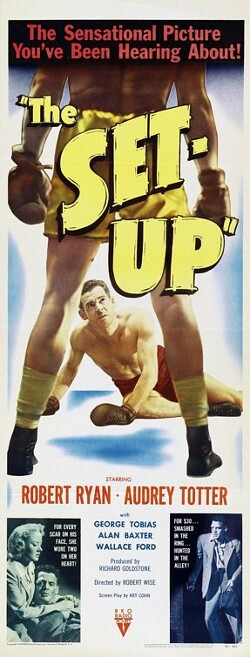

- (tie) The Set-Up (1949, Robert Wise)

The Set-Up is a short but near perfect distillation of the film noir, with many of the key elements but with a big dose of heart. The camera roves through one space in real time (this was one of the first films to play out in real time), powerfully conveying the limited choices open to Robert Ryan’s aging boxer. He is certain that he has one more good fight in him and his self-belief wins through only for there to be consequences thanks to his double-dealing manager. Ryan, in what is undoubtedly his best performance, gives the film hope and an emotional connection where otherwise it would be merely harshly realistic and relentlessly down-spirited. Brilliantly shot, you can see traces of The Set-Up in later great boxing films such as Raging Bull and Fat City. (Matthew McKernan)

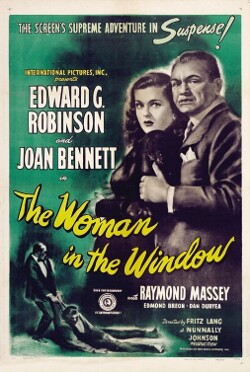

- (tie) The Woman in the Window (1944, Fritz Lang)

One of the great ‘despair’ noirs, The Woman in the Window unfolds with a horridly inescapable determinism. Unlike the other Lang/Robinson/Bennett/Duryea noir Scarlet Street, which is about cruel people being cruel to a dopey innocent, The Woman in the Window is effective because Robinson’s fall is so inevitable. When we first see him, his lecture theater blinds have put him behind bars and he remains imprisoned in one way or another throughout the film. The Woman in the Window also has one of the best double-endings ever, both satisfying conclusions to different facets of the film: one completing Robinson’s cruel fate to devastating effect and the other concluding Robinson’s study of a trapped, mild-mannered nobody. (Matthew McKernan)